Digital preservation is about preserving digital objects. These objects have to come to be somehow and earlier this week (Wednesday 9th February) I was invited to talk at an Approaches to Digitisation course facilitated by Research Libraries UK and the British Library. It was held at the British Library Centre for Conservation, a swanky new building in the British Library grounds. It was the first time the course has run, though they are planning another in the autumn. The course was aimed at those from cultural heritage institutions who are embarking on digitisation projects and sought to provide overview of how to plan for and undertake digitisation of library and archive material.

British Library by Phil Of Photos

I was really pleased that the event spent a considerable amount of time on the broader issues. Digitisation itself, although not necessarily easy, is just one piece of the jigsaw and there has been a tendency in the past for institutions to carry out mass digitisation and not consider the bigger picture. During the day several speakers advocated the use of the lifecycle approach and planning, selection and sustainability were highlighted as being key areas for consideration. If digitisation managers take this on board the end result will hopefully be a collection of well-rounded, well-maintained, well-used digitised collections with a preservation strategy in place.

The course followed a fairly traditional format with presentations, networking time and a printed out delegate pack. Unfortunately there was no wireless but this left us concentrating completely on presenters and what they had to say, and it was all very useful stuff.

Benefits of Digitising Material – Richard Davies, British Library

Richard Davies started the day with an introduction to the benefits of digitisation (a good article entitled The Case for Digitisation is available on P16 of the most recent JISC inform). Rather than just giving a straightforward overview of the different benefits he used a number of case studies to illustrate the added value that digitisation can provide, for example by opening up access, allowing digital scholarship and collaboration.

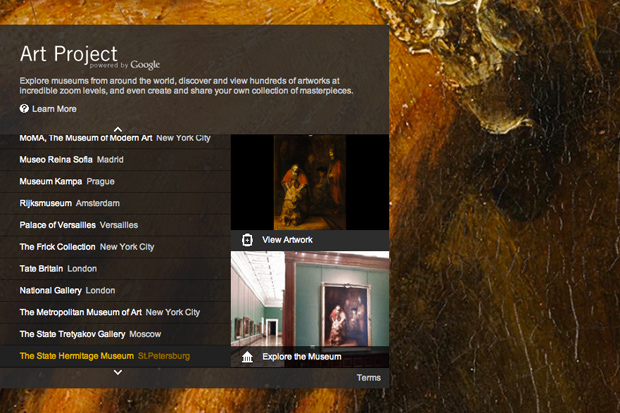

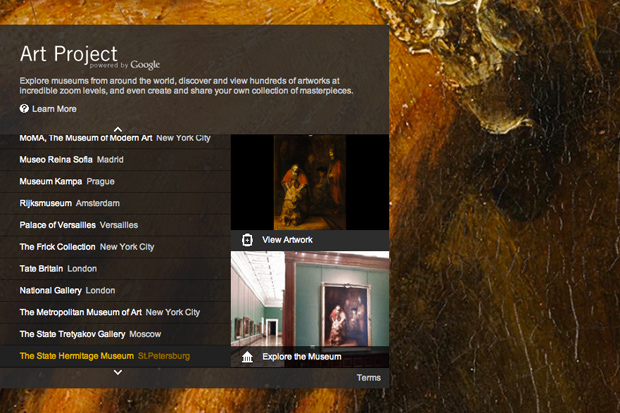

The British Library has now digitised approximately 4 million news papers. Opening up access has meant that people can use the papers in completely different ways, for example by full text searching and allowing different views on resources. Projects like the British Library Beowulf project and others allow extensive cross searching and the Codex Sinaiticus project has taken a bible physically held in 4 locations and allowed it to be accessed as one, for the first time. The Google Art Project allows users to navigate galleries in a similar way to Google Street view and the high resolution of the digital objects is impressive.

Google Art Project

Digitisation also presents opportunities for taking next step in digital scholarship. In the past carrying out the level of research that now possible with digital resources would have taken a very long time indeed. The Old Bailey project has digitised 198,000 records and users can now carry out extensive analysis on content in a matter of minutes.

Davies also illustrated how digitisation can allow you to expand your collection by bringing in resources from general public and by crowd sourcing. The Trove Project has carried out crowd sourcing of its optical character recognition (OCR) results. They have offered prizes for people who corrected the most text, they have also made a lot of details of how they went about the project is available online. The Transcribe Bentham project have also made many details about how they carried out work available on their blog.

Davies suggested that digitisation managers need to think about the model they will be using. Will content be freely available or will there be a business model behind it. One option is to allow users to dig to a certain level and then ask them to pay if they wish to access any further resources.

Davies concluded that to have a successful digitisation project you need to spend time on the other stuff – metadata, OCRing the text, making resources available in innovative ways. Digitisation is only one element of a digitisation project.

Planning for Digitisation- Richard Davies, British Library

Richard Davies continued presenting, this time looking more at his day job – planning for digitisation projects. He offered up a list of areas for consideration (though stated that this was a far from exhaustive list).

He suggested that a digitisation strategy helps you prioritise and can be a way of narrowing down the field. Such a strategy should fit within a broader context, in the British Library it is part of their 2020 vision. Policy and strategy should consider questions like: Who are we? Where could we go? Where should we go? How do we get there? It should also bear in mind funding and staffing levels.

Davies also spent a lot of time talking about the operational and strategic elements of embarking on a project. It is very much a case of preparation being the key, he suggested digitisation managers do as much preparation up front as possible without holding up the project. For example when considering selection consider what’s unique? What’s needed? What’s possible? (bearing in mind cost, copyright, conservation). He also emphasised the importance of lessons learnt reports.

Davies concluded by talking about some current challenges to digitisation programmes. The primary one was economic as funding calls are rarer and rarer. It can be useful to have funding bid expert onboard. He also explained that you can make the most of the bidding process by using it as an opportunity to help yourself to answer difficult questions about what you want to do. There is currently a lot of competition for funding. The last JISC call (Rapid Digitisation Call) offered up £400,000 worth of funding, 7 projects were funded, 45 bids were received.

Davies also highlighted that digital preservation and storage are increasingly becoming problems. Sustainability need not be forever but you should at least have a 3 – 5 year plan in place.

I was also pleased to hear Davies highlight a project I am now working on: The IMPACT project, funded by the European Commission. It aims to significantly improve access to historical text and to take away the barriers that stand in the way of the mass digitisation of the European cultural heritage

Use of Digital Materials – Aquilies Alencar Brayner, British Library

After a coffee break Aquilies Alencar-Brayner considered how users are currently using digital materials. He mentioned research by OCLC that states that students consistently use search engines to find resources rather than starting at library Web sites. They are also using the library less as books are still the brand associated.

Alencar-Brayner ran through the 10 ‘ins’ that users want: integrity, integration, interoperability, instant access, interaction, information, ingest of content, interpretation, innovation and indefinite access.

He showed us some examples of how the British Library is carrying out work facilitating access to digital materials for example through the Turning the Pages project which will allow you to actually turn the page, magnify the text, see the text within context, listen to audio.

Codex Sinaiticus

Where to begin? Selecting resources for digitisation Maureen Pennock, British Library

Maureen Pennock introduced us to selection. She explained that selection is usually based on previously selected resources and commonly the reason given for selection is for improving face access. However sometimes the reason can be for conservation of original and occasionally it is for enabling non-standard uses of resource.

Pennock explained that selection is often based on the appraisal made for archival purposes, known as assessment – areas for consideration include suitability and desirability and whether they are what users need.

Selection is an iterative process and revisited several times after you’ve defined your final goals and objectives. It is important to identify internal and external stakeholders such as curators, collection managers and so on and include them in the process.

Once you’ve set a scope you will need to pre select items, but there is no one size fits all approach. Practical and strategic issues come into play and items will need to be assessed and prioritised.

Pennock explained that suitability will need to consider areas like intellectual justification, demand, relevance, links to organisational digitisation policy, sensitivity, potential for adding value (e.g. commercial exploitation of resources).

Alongside suitability there will need to be item assessment looking at the quality of the original, the feasibility of image capture, the integrity and condition of resources, complex layouts for different material types, historical and unusual fonts and the size of artefacts. Legal issues such as copyright, data protection, licences, IPR also have a role to play.

Pennock concluded that not all issues are relevant to everyone and some with have more weighting than others. Practitioners will need to decide on their level of assessment and define their shortlist. It is important that you can justify your selection process in case issues arise later down the line.

Metadata Creation, Chris Clark, British Library

To wet our appetite for lunch Chris Clark took us on a whirlwind tour of digitisation metadata and its value. He explained that metadata adds value unfortunately often left at the end with tragic consequences. He also warned us that there is still no commonly agreed framework and it is still an immature area. Quite often metadata’s real value is most realised in situations where it isn’t expected. Clark recommended Here comes Everybody by Clay Shirky as a text that illustrated this. He also suggested delegates look at the One to Many; Many to One: The resource discovery taskforce vision.

Metadata is a big topic and Clark was only able to touch the surface. He advised us to think of metadata as a lubricant or adhesive that holds together users, digital objects, systems and services. We could also see metadata as a savings account – the more you put in more you get out.

Clark then offered us a quick introduction to XML and some background to the most relevant types of metadata when it comes to digitisation (descriptive, administrative, structural) metadata. He explained that Roy Tennant OCLC had characterised 3 essential metadata requirements: liquidity (written once use many times, expose), granularity and extensible (accommodate all subjects).

Clark concluded with an example of a high level case study he had worked on: Archival Sound Recordings at the British Library. On the project they had passed some of the load to the public by crowd sourcing recording quality and asking people to add tags and comments.

Preparing Handling Guidelines for Digitisation Projects, Jane Pimlott, British Library

After a very enjoyable lunch Jane Pimlott provided a real-world case study by looking at a recent project on which the British Library had created training and handling guidelines for a 2 year project to scan 19th century regional newspapers. It had been an externally funded project but work carried out on premises at Colindale. The team had had 6 weeks in which to deliver a training project, though a service plan was already in place and contractors were used.

Pimlott explained that damage can occur even if items are handled carefully but that material that is in a poor condition can be digitised but can take longer. She explained the need to understand processes and equipment used – e.g. large scale scanners. Much of the digitisation team’s work had been making judgement calls on assessing the suitability of items for scanning for the newspaper project. Their view was that canning should not be at expense of the item, it should not be seen as last chance scanning. Pimlott concluded that different projects present different risks and may require different approaches to handling and training.

Preservation Issues, Neil Grindley, JISC

Finally the day moved in to the realm of digital preservation. Neil Grindley from JISC explained how he had come from a paper, scissors, glue and pictures world (like many others there) but that the changing landscape required changing methods.

He began by trying to find out whether people considered digital preservation to be their responsibility. Unsurprisingly few did. He explained that digital preservation involves a great deal of discussion and there is lot of overlapping territory, it is best undertaken collaboratively. Career paths are only just beginning to emerge and the benefits are hard to explain and quantify. He revealed that a recent Gartner report stated that 15% of organisations are going to be hiring digital preservation professionals in the future, so it is a timely area in which to work in. Despite this is still tricky to make a business case to your organisation for why you should be doing it.

Grindley explained that there are no shortage of examples of digital preservation out there; recent ones include Becta and Flickr.

Grindley then went on to make the distinction between bit preservation and logical preservation. Bit preservation is keeping the integrity of the files that you need. He asked is bit preservation just the IT departments back up? Or is it more? He saw the preservation specialist as sitting between the IT specialist and content specialist almost as a go-between.

Used the example of Heydegger showing pixel corruption, corruption is both easy and potentially dangerous – especially in scientific research areas.

Grindley took us on a tour of some of the most pertinent areas of digital preservation such as checksums. These are very important for bit preservation and ensure that when you use something and go back to you can check that the files are not corrupted or changed. It is very easy to see if a file has been tampered with over time. Some of the tools suggested include:

Grindley then considered some of the main digital preservation strategies: technology preservation, emulation, migration, which led him on to the subject of logical digital preservation – not just focussing on keeping the bits but looking at what the material is and keeping its value

To conclude Grindley looked at some useful tools out there including DROID – digital record object identification, Curators workbench – useful tool from University of North Carolina, creates a MODS description and Archivematica – comprehensive preservation system. He also touched on new JISC work in this area.

5 new preservation projects starting Feb – July 2011

Other Sources of Information, Marieke Guy, UKOLN

I concluded the day by giving a presentation on other sources of information on digitisation and digital preservation. My slides are available on Slideshare and embedded below.

I think by now the delegates had had their fill of information but hopefully some will go back and look at the resources I’ve linked to.

To conclude: I really enjoyed the workshop and found it extremely useful. If I have one criticism it’s that the day was a little heavy on the content side and might have benefited from a few break-out sessions – just to lighten it up and get people talking a little more. Maybe something for them to bear in mind for next time?

A while back I mentioned that the Software Preservation Study team were running a free workshop for digital curators and repository managers to understand and discuss the particular challenges of software preservation.

A while back I mentioned that the Software Preservation Study team were running a free workshop for digital curators and repository managers to understand and discuss the particular challenges of software preservation.