This guest blog post is written by Margaret Adolphus, a journalist specialising in librarianship, the knowledge industry and higher education, and currently researching an article on public library websites.

I’d come across Margaret’s request for information in CILIP Gazette in August 2009 and featured it in my post entitled Why are Library Web Sites so Dull?. When I contacted Margaret recently to find out just what sort of feedback she had had and whether she had come to any conclusions, I was pleased when she offered to write this guest blog post.

Contact Margaret at margaret@adolphus.me.uk or on 01525 229487.

*****************

Earlier this year I put the following question to readers of CILIP Gazette (31 July – 13 August 2009 issue):

Why is it that public library websites are so often so dull compared with their American counterparts, and why do they make so little use of social media, inviting comment and participation from their publics?

I received several responses, mostly from librarians who were frustrated by interference from the local authority for whom they worked. The latter had a web blueprint which they wanted all their service departments to follow, regardless of whether they were promoting culture or collecting refuse. Even the content of library websites was sometimes re-written (by people who were also writing about re-cycling, rights of way and parks maintenance, and who were not professional librarians), whilst also being subject to the dictates of the branding police.

Other respondents, however, had managed to circumvent their local authority masters to produce highly creative web solutions: The Idea Store in Tower Hamlets, and Tales of One City in Edinburgh being two such examples.

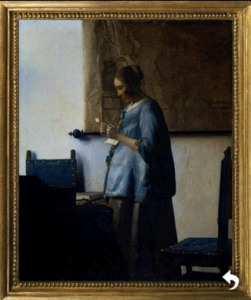

Edinburgh City Library homepage:

Edinburgh Tales of One City

And, on the other side of the Atlantic, public libraries have much more engaging and interactive sites, with creative use of images, rich media and social media – resulting in a site which was both appealing and engaging.

Darien Libraries (USA) homepage:

darien library homepage

An avid reader, I’m often on our library website, but to order books recommended elsewhere. I would not browse in the way that I browse Amazon for recommendations. And yesterday, when I wanted to know the percentage of those living below the poverty line in Namibia, I consulted the Internet, not the reference librarian (although I’ve subsequently discovered their excellent collection of subscription works).

I’m a natural library user – middle aged and book loving. But most of the rest of the population, especially those in a younger age group, are used to 24/7 opportunities for information and entertainment, and commercial websites which offer browsing and personalization. So it’s vital that public libraries enhance their virtual presence to appeal to this wider demographic, if they are not to lose them.

We are living in an age when the web is not just for information or commercial transaction: it’s a place for social exchange. Ordinary people can write and be published on the web without the expense of constructing a web site; they can meet one another, chat and have discussions. Information is no longer top down, delivered by an authority from above, but something that anyone can contribute to. Evidence for this is seen not just in blogs and social networking sites, but also in formal collections of information such as library catalogues. Some libraries, for example, are introducing local community information into their catalogues, hence both harnessing collective intelligence and providing a social service.

One of the complaints voiced to me after the Gazette piece was that people felt disempowered by what they perceived as ICT control over their website. One librarian commented: ‘a library website should belong to the library first, but it inevitably ends up being a mouthpiece for council services, rather than an important tool for developing the library offering’.

In an era when library managers – as are those of all council services for that matter – are having to cut costs and increase services, going virtual is an objective which will not only meet people where they are, but also save costs. The virtual library can enable self service, with people searching the catalogue and putting in their own requests, renewing their books etc. – thereby reducing the number of staff needed on the front desk. Reference works can be put online, so that library subscribers can browse accredited works without having to ask the reference librarian.

So, it makes good sense for library managers to redirect their staff towards web services, which in these days of easy to use content management systems, do not require a lot of technical expertise. And, as the trend is for more council services to be outsourced, doesn’t it also make sense for the council to allow the library to do its own thing?

My research into why more libraries are not putting more effort into their virtual services is ongoing, and I would welcome comment on this piece as well as any experiences, good or bad, that you wish to share.

Contact Margaret at margaret@adolphus.me.uk or on 01525 229487.

As I was using my iPod Touch to view the overnight tweets I was able to follow the link and install the application.

As I was using my iPod Touch to view the overnight tweets I was able to follow the link and install the application.