Introduction

This document provides some approaches to selection for preservation of Web resources.

Background

Deciding on a managed set of requirements is absolutely crucial to successful Web preservation. It is possible that, faced with the enormity of the task, many organisations decide that any sort of capture and preservation action is impossible and it is safer to do nothing.

It is worth remembering, however, that a preservation strategy won’t necessarily mean preserving every single version of every single resource and may not always mean “keeping forever”, as permanent preservation is not the only viable option. Your preservation actions don’t have to result in a “perfect” solution but once decided upon you must manage resources in order to preserve them. An unmanaged resource is difficult, if not impossible, to preserve.

The task can be made more manageable by careful appraisal of the Web resources, a process that will result in selection of certain resources for inclusion in the scope of the programme. Appraisal decisions will be informed by understanding the usage currently made of organisational Web sites and other Web-based services and the nature of the digital content which appears on these services.

Considerations

Some questions that will need consideration include:

- Should the entire Web site be archived or just selected pages from the Web site?

- Could inclusion be managed on a departmental basis, prioritising some departmental pages while excluding others?

You will also be looking for unique, valuable and unprotected resources, such as:

- Resources which only exist in web-based format.

- Resources which do not exist anywhere else but on the Web site.

- Resources whose ownership or responsibility is unclear, or lacking altogether.

- Resources that constitute records, according to definitions supplied by the records manager.

- Resources that have potential archival value, according to definitions supplied by the archivists.

Resources to be Preserved

(1) RECORD

A traditional description of a ‘record’ is:

“Recorded information, in any form, created or received and maintained by an organisation or person in the transaction of business or conduct of affairs and kept as evidence of such activity.”

A Web resource is a record if it:

- Constitutes evidence of business activity that you need to refer to again.

- Is evidence of a transaction.

- Is needed to be kept for legal reasons.

(2) PUBLICATION

A traditional description of a publication is:

“A work is deemed to have been published if reproductions of the work or edition have been made available (whether by sale or otherwise) to the public.”

A Web resource is a publication if it is:

- A Web page that’s exposed to the public on the Web site.

- An attachment to a Web page (e.g. a PDF or MS Word Document) that’s exposed on the Web site.

- A copy of a digital resource, e.g. a report or dissertation, that has already been published by other means.

(3) ARTEFACT

A Web resource is an artefact if it:

- Has intrinsic value to the organisation for historical or heritage purposes.

- Is an example of a significant milestone in the organisation’s technical progress, for example the first instance of using a particular type of software.

Resources to be Excluded

There are some resources that can be excluded such as resources that are already being managed elsewhere e.g. asset collections, databases, electronic journals, repositories, etc. You can also exclude duplicate copies and resources that have no value.

Selection Steps

Selection of Web resources for preservation requires two steps:

- Devise a selection policy- defining a selection policy in line with your organisational preservation requirements. The policy could be placed within the context of high-level organisational policies, and aligned with any relevant or analogous existing policies.

- Build a collection list.

Selection Approaches

Approaches to selection include:

- Unselective approach

- This involves collecting everything possible. This approach can create large amounts of unsorted and potentially useless data, and commit additional resources to its storage.

- Thematic selection

- A ‘semi-selective’ approach. Selection could be based on predetermined themes, so long as the themes are agreed as relevant and useful and will assist in the furtherance of preserving the correct resources.

- Selective approach

- This is the most narrowly-defined method which does tend to define implicit or explicit assumptions about the material that will not be selected and therefore not preserved. The JISC PoWR project recommend this approach [1].

Resource Questions

Questions about the resources which should be answered include:

- Is the resource needed by staff to perform a specific task?

- Has the resource been accessed in the last six months?

- Is the resource the only known copy, or the only way to access the content?

- Is the resource part of the organisation’s Web publication scheme?

- Can the resource be re-used or repurposed?

- Is the resource required for audit purposes?

- Are there legal reasons for keeping the resource?

- Does the resource represent a significant financial investment in terms of staff cost and time spent creating it?

- Does it have potential heritage or historical value?

An example selection policy is available from the National Library of Australia [2].

Decision Tree

Another potentially useful tool is the Decision Tree [3] produced by the Digital Preservation Coalition. It is intended to help you build a selection policy for digital resources, although we should point out that it was intended for use in a digital archive or repository. The Decision Tree may have some value for appraising Web resources if it is suitably adapted.

Aspects to be Captured

It is possible to make a distinction between preserving an experience and preserving the information which the experience makes available.

Information = content (which could be words, images, audio, …) Experience = the experience of accessing that content on the Web, which all its attendant behaviours and aspects

Making this decision should be driven by the question “Why would we want to preserve what’s on the Web?” When deciding upon the answer it might be useful to bear in mind drivers such as evidence and record-keeping, repurposing and reuse and social history.

References

- JISC PoWR, <http://jiscpowr.jiscinvolve.org/>

- Selection Guidelines for Archiving and Preservation by the National Library of Australia, National Library of Australia, <http://pandora.nla.gov.au/selectionguidelines.html>

- Digital Preservation Coalition Decision Tree, Digital Preservation Coalition, <http://www.dpconline.org/graphics/handbook/dec-tree-select.html>

]]>

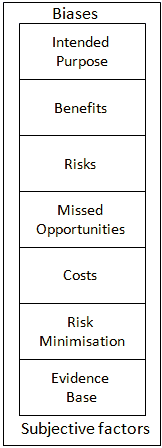

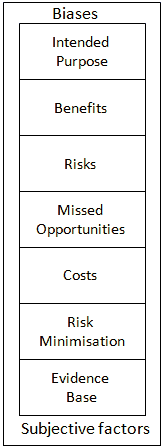

The Risks and Opportunities Framework aims to facilitate discussions and decision-making when use of innovative services is being considered.

The Risks and Opportunities Framework aims to facilitate discussions and decision-making when use of innovative services is being considered. This framework aims to facilitate discussions and decision-making when use of Social Web service is being considered.

This framework aims to facilitate discussions and decision-making when use of Social Web service is being considered.

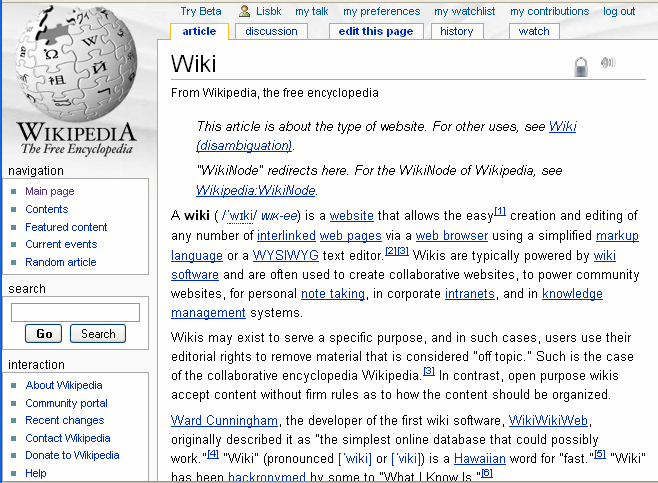

Seesmic video posts can be viewed using a Web browser, either by visiting the Seesmic Web site or by viewing a Seesmic video post which has been embedded in a Web page.

Seesmic video posts can be viewed using a Web browser, either by visiting the Seesmic Web site or by viewing a Seesmic video post which has been embedded in a Web page. For many the initial experience with a micro-blogging service is Twitter. Initially many users will make use of the Twitter interface provided on the Twitter Web site. However regular Twitter users will often prefer to make use of a dedicated Twitter client, either on a desktop PC or one a mobile device such as an iPhone or iPod Touch.

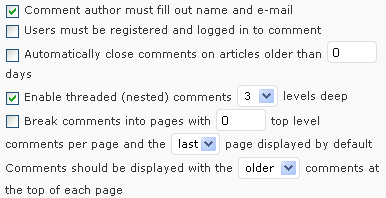

For many the initial experience with a micro-blogging service is Twitter. Initially many users will make use of the Twitter interface provided on the Twitter Web site. However regular Twitter users will often prefer to make use of a dedicated Twitter client, either on a desktop PC or one a mobile device such as an iPhone or iPod Touch. You may wish to provide additional content on your blog. This might include additional pages or content in the blog’s sidebar, such as a ‘blogroll’ of links to related blogs or blog ‘widgets’. An example of the administrator’s interface for blog widgets on the UK Web Focus blog is shown.

You may wish to provide additional content on your blog. This might include additional pages or content in the blog’s sidebar, such as a ‘blogroll’ of links to related blogs or blog ‘widgets’. An example of the administrator’s interface for blog widgets on the UK Web Focus blog is shown. The diagram shows growth in visits to the UK Web Focus blog since its launch in November 2006, with a steady increase in numbers (until August 2007 when many readers were away).

The diagram shows growth in visits to the UK Web Focus blog since its launch in November 2006, with a steady increase in numbers (until August 2007 when many readers were away).